Günther Schlee

I have been invited to write another blog entry on corona in Northeast Africa to follow up on earlier reports (ReCentGlobe Blog Part1 & Part 2, Oxford Blog). But how can one write about corona when there are so many apparently more burning issues? Since early November, rival armies have been fighting each other, and behind them, militias and armed civilian mobs massacring people move through Tigray, a federal state in northern Ethiopia.

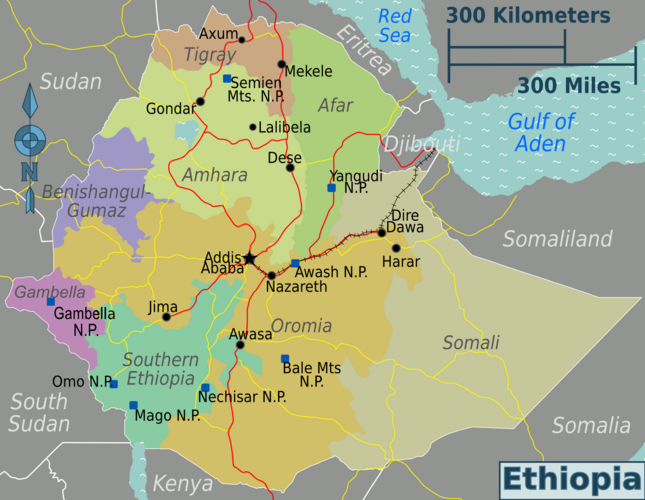

Well, also these terrifying events are connected to corona. Although it is far from being the deeper cause of the violence, corona has been part of the chain of events that triggered it. The prime minister Abiy Ahmed (yes, the same person who won the Nobel Prize for Peace last year) has come to power in April 2018 because the ruling coalition in Ethiopia needed to widen its power base. Because of the plans for urban development around the capital Addis Ababa, in areas that belonged to the federal state of Oromia and were predominantly inhabited by Oromo, there was massive unrest triggered by land expropriations. To mollify the Oromo opposition, it was thought to be a good idea to have an Oromo prime minister. Things did not quite work out that way. Until the recent outbreak of violence in the north, divisions among the Oromo community in the central and western parts of the country appeared to be the worst problem of Ethiopian politics.

Where does corona come in? Abiy has come to power by a reshuffle in a coalition. Full legitimacy could only be provided by elections. With the outbreak of corona, these elections were postponed indefinitely. His supporters say that that was because of his concern for public health, whereas his critics say it was due to the fact that he would not have won the elections.

In Tigray, there had been growing dissatisfaction. The Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) , which had been the dominant part of the ruling coalition at the national level since 1991, was now sidelined, especially since the coming into power of Abiy. Its power was now limited to the Tigray Regional State alone. In defiance of the rulings at the national level, elections were carried out in Tigray independently. This was perceived by the central government as a separatist action that was illegal because the procedures laid down in the constitution for a state to leave the federation were not followed (In fact, these procedures do not make it possible for a one-sided separation from the federation, although the “right to separation” is celebrated in pluralist Ethiopian political rhetoric). The federal army then moved into Tigray, according to the government in Addis in response to a TPLF attack against a base of the federal army in Tigray. What precisely happens there is difficult to know because telephone and internet connections have been cut, as before in western Oromia.

The refugee camps in eastern Sudan, which date back to the time before 1991 and then gradually shrunk as the situation in Ethiopia stabilized and as people went back to Ethiopia, are now filling up again. The number of refugees has quickly reached 50,000. These were mostly ethnic Tigray, but they comprised also Amhara. Tigray and Amhara have been relocated to different neighbourhoods to prevent mutual revenge attacks. Families have been separated, and people are worried whether their loved ones are still alive. Corona may be the least of their worries. But one might think that the crowded conditions under which they live, their weakened state, and constant intermingling provide the ideal conditions for the spread of the virus. Others think that dry heat and high ultraviolent radiation inhibit the transmission of the virus within Sudan. Let us hope that that is so. Little is known about the fate of 96,000 Eritrean refugees in Tigray. The Addis Ababa government is now in a military alliance with the Eritrean government against the TPLF and stopped supplies to the refugees, who are seen as dissidents. The TPLF has withdrawn into the mountains and the UN has no access to the camps. Whether hunger or corona will take the higher toll among the Eritrean refugees stranded in Tigray is anyone’s guess.

This is not the first time that Ethiopians suffer from the combined effect of corona and violence. While in Tigray, the closely related, Semitic-speaking Amhara and Tigray massacre each other; in the western state of Beni Shangul, many members of the local ethnic groups put both of them in the same category as “Highlanders” and regard them as intruding strangers.

Yohannes Yitbarek reports that in Metekel (see map below), already in October, innocent people have been killed. On 14 October alone, “over 20 people [were] killed, hundreds wounded, and most [Highlander] people are fleeing their homes.” His earlier reports show that destitution and anger had built up over some time. In the second part of this series, we have learned how restriction to movements were introduced in Beni Shangul. The consequences for certain segments of the population were immediate.

Here are some excerpts from Yohannes’s diary:

Saturday, April 18

In Gelgel Beles town, the local authorities have taken advantage of the lockdown to redesign the informal economy. Smaller businesses – coffee shops and roadside restaurants – have been demolished. The operation was a directive from the municipality of the town – supported by the police – which stated that informal markets were potential hotspots for the spread of Covid-19.

Tuesday, April 21

On Tuesday afternoon, when I and my friend Berhan went to the center of the town, only few people were on the street. The ladies who make coffee on the streets for selling were out of sight. The shoeshine boys who make their living on the streets of Gelgel Beles had gone to their homes.

We met Tilahun on the street and he told us what he had observed an hour ago on the main road. He said, “those ladies who started making coffee and who arranged seats for their customers were forcefully chased by the police”.

As we go back home, I and Berhan were discussing issues pertaining to the negative impacts of Covid-19–related restrictions on the daily lives of people in the informal economic sectors. Despite the strict rules which require people to stay at home, laborers who live hand-to-mouth have no choice but to face the delicate balance of hunger and contraction of Covid-19. Unlike workers in the formal systems who are guaranteed some social security during the lockdown, informal workers – like the coffee vendors on the streets and the shoeshine boys – are not eligible for such social protection.

Wednesday, April 29

The closure of the main market took effect on 17 April and has been so for more than ten days now. The Command Post Office recently announced through a circular that small business will still be closed until such time the risk from Covid-19 would decrease. This decision has resulted in determined resistance from the side of the people working in the informal economic sector, as many women and men have lost their daily income.

For Tigist, owner of a coffee shop on the roadside, the demolition is considered as an attack on her basic livelihood. She told me that such actions from the local government have not been new to her and others, as the government chases them away every now and then. According to Tigist, the reason behind this action is crystal clear – to replace the unregistered business with the registered once. Like her, Selam also believes that the government used Covid-19 as a pretext to demolish the source of their livelihoods.

Thursday, April 30

Fruit and vegetable vendors whom I talked to have expressed dissatisfaction at the current situation. They have no space to lay out their products, and they are also prohibited to bring their produce by the road. They have made pleas to authorities to have some proper system in place during this difficult time. Semira, a 45-year-old woman who sells banana and mango in front of her house, told me that she is finding it very hard to make a living in this difficult time. She is widowed and raising four children; the only source of income for the family is from her daily sales.

Monday, May 4

As the recovery of the two people in the neighbouring towns of Amhara region is announced, restrictions which have been put in effect in my hometown begun to loosen up. In the third week, street vendors and others who run small scale businesses have returned to their former places. The ones whose small huts were demolished have started to put new pavilions on the verandas of their house. But the challenge now remains the absence of customers.

Belayneshe felt despair as she watched her fruits decayed. Because of fear of Covid-19, there were no buyers. Every morning, she piles her basket with fruit and takes it to the main road. Although she is permitted to sell her produce on the streets, she said customers are too afraid to come to her place. “If I was afraid of corona, I and my three children would die”, she said, adding: “If I obey the rule ‘stay home’, I and my children will die of hunger. Coming to my workplace is the ‘lesser evil.’”

While the economic consequences of the anti-corona measures were immediate, the pandemic itself was slow in coming, or so it was perceived. The numbers of tests are low, and one does not know whether the low figures in Ethiopia or Sudan are statistical artefacts or reflect the actual situation. Be that as it may, the fear of corona receded in many places.

On 28 October, Kebede wrote from Konso (see map below): “The schools have opened again and people live as usually. It seems there is no problem. No corona in Konso.”

Like in the north and the west of Ethiopia, in Konso, the worry about corona has been overshadowed by a violent ethnic conflict. Here, it is between Konso, in the narrow sense, and the Ale, who had been regarded as a section of the Konso and who now claim the status of being a separate ethnic group. Since the 1990s, such claims at different levels (getting a separate district, a zone within a state, or even a separate state within the federation) have been rewarded with new political offices and new government infrastructures. Of course, all this happens at the expense of the taxpayer.

That corona was not experienced as a reality in many places strengthened the belief of numerous people that the virus was just a pretext for the government to delay the elections, and that takes us back to the sad story about Tigray at the beginning of this blog entry. The economic disruption caused by the anti-corona measures and the suspicion that corona was not real both have had their share in destabilizing Ethiopia.

Today's contributiondraws on accounts by Solomon Erjabo who reports from Hosana (Hadiya);Yohannes Yitbarek who is based at Pawi in the Metekel Zone of BeniShangul-Gumuz State, and above all, by Saleh Said, writing from Hayk*in southern Wollo. (For more information see the caption of the map inthe first part of this series.)