In the 2015 movie The Martian, the astrobotanist Mark Watney, who was stranded on Mars with limited food supplies, designed an improvised garden to grow potatoes. In the plot, Watney used one of the airlock rooms as his “greenhouse”, brought in soil from the surface of Mars, used the crew’s biowaste as soil fertilizer, and produced water by burning hydrazine. Watney thereby created a closed agricultural system that allowed him to grow potatoes on Mars. While this science fiction movie (and the book on which it is based) presents a far-fetched reality of farming on Mars,[1] it does represent a popular knowledge indicator of the anxiety of the world right now as well as the ambitions of humanity. While flamboyant billionaires like Elon Musk and Richard Branson are attempting to conquer space, the global debate has, in recent decades, turned towards the future of food and the capacity of the current agri-food system to feed a growing world population, which is expected to reach nine billion people by 2050. While alternative food sources, such as algae, artificial meat, or insects, are being explored by scientists across the globe, technological innovations and agricultural technologies (AgTech) are occupying an evergrowing space in the debate. In a similar fashion to Watney’s farm, controlled environmental agriculture (CEA) – that is, a closed structure such as a greenhouse, a building, or a warehouse where ideal growing conditions are maintained for the optimal development of the crop – is bourgeoning across geographies. CEA is promising to tackle the challenges faced by the global agri-food system by optimizing the use of resources such as water, energy, space, and labour while, at the same time, increasing yields.

In places like the Netherlands and Silicon Valley, AgTech companies (and start-ups), AgTech farms, and tech providers are offering a wide range of solutions for the sustainability and management issues facing the agri-food sector. In this sector, new tools and knowledge fields – such as robotics, precision agriculture, big data, automation, biotechnology, smart farming, controlled environmental farming, lights, and drones – are being developed. These innovations act simultaneously on collecting, analysing, and evaluating the data and are used to guide decision-making at the farm level, using a smaller amount yet more precise use of input for higher yields. In a matter of decades, the places where these tools are developed have emerged to become global leaders in such farming technologies as well as innovations hub in the agri-food sector. The hubs where cerebral “geeks” birthed Google, Amazon, or Tinder are now teeming with people discussing corn yields and optimal honey production.

Recently, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has been working very hard to join the race for AgTech innovation. This relatively small Middle Eastern nation – an oil-rich country located in the Arabian Gulf region – is endowed with extremely limited arable land, scarce water resources, rainfall that rarely exceeds 80 mm per year, and extreme temperatures. While 80 to 90 per cent of its food requirements are imported, the UAE aims (very ambitiously as many would agree) to become the most food-secure country in the world by 2051 – based on the Global Food Security Index[2] – while, at the same time, becoming the most technologically advanced place for agricultural innovation. To this end, the government and the Ministry of State for Food and Water Security are devoting considerable effort to enhance local food production using technological innovation. Tellingly, the Minister of State for Food and Water Security declared in an interview in 2018: “We are trying to create the equivalent of Silicon Valley – but with food” (“UAE Minister Talks Plans to Build a ‘Silicon Valley’ of Food Technology”, 2018). This represents the ambition of the UAE’s government to transform the desert into a green tech oasis.

AgTech in the UAE: A Convergence of Global Actors

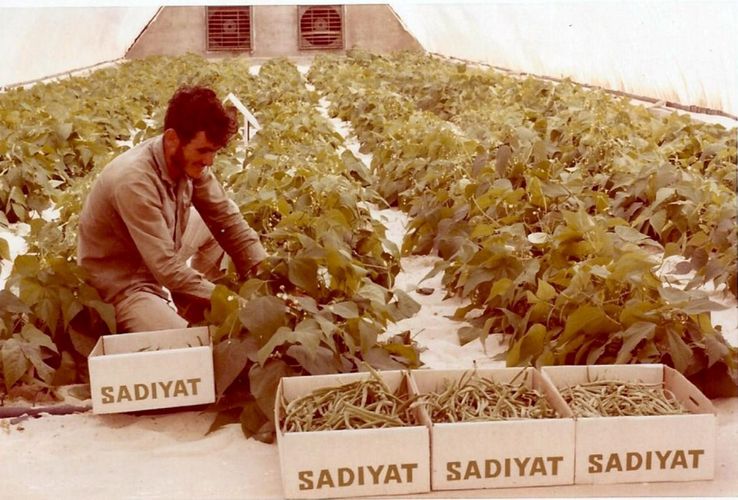

Agriculture development in the UAE has been on the agendas of policy-makers since the mid-twentieth century. After the British colonial power introduced in the 1960s the possibility of commercial farming (MacLean, 2017), Sheikh Zayed Al Nahyan (ruler of the emirate of Abu Dhabi and president of the UAE from 1971 until his death in 2004) entered the country in a large-scale AgTech venture beginning in the early 1970s. In collaboration with the University of Arizona, Sheikh Zayed launched the Arid Land Research Center on Saadiyat Island in Abu Dhabi. There, a team of scientists developed high-tech greenhouse structures used for a combined purpose of vegetable production, water desalination, and electricity generation (Fenelon, 1973; Koch, 2019) – see figures 2 and 3 (below). According to rumours at the time, an aide to Sheikh Zayed read about the University of Arizona’s successful project in Mexico, where vegetables were grown using a hydroponic system. Upon showing the project to the ruler, Sheikh Zayed became so excited that he requested such a farm to be built in the UAE (Dennehy, 2019; Koch, 2019). With a total investment budget of USD 3.4 million provided by the emirate of Abu Dhabi, a 20,000 m2 site was selected on Saadiyat Island at the exact location where the museum Louvre Abu Dhabi now stands. The construction started in 1969, under the supervision of Dr. Merle Jensen, a horticulturist and hydroponic expert from the University of Arizona. In the early 1970s, a variety of vegetables were grown to feed the local community. However, by the end of that decade, the project was no more: the greenhouses had been dismantled, and little information exists with regard to the development of similar farms or the reason of its failure – albeit some research points toward a combination of a lack of funding and of conflicting visions about to the future of the Island (Koch, 2019). In the space of a decade, the ambitious, forward-looking project mysteriously disappeared from the face of the earth, as if the surrounding sand dunes had all of a sudden eaten it up.

For those aware of the existence of the Saadiyat greenhouses, the 2010s carry an air of déjà vu. The greenhouse received extensive news coverage at the time, and it seems that the UAE is at it again after a hiatus of a few decades. Like some crop-threatening fungus, recent media headlines on AgTech innovation in the UAE seem to proliferate. With titles such as “Crop One’s Mission Is to Solve the World’s Food Problems One Crop at a Time”, “Pure Harvest Wants to Grow Tomatoes in the Desert”, “From Sand to Soil: Chinese Researchers Plan to Turn the Abu Dhabi Desert Green”, “Generation Start-up: The Mission to Grow Tasty Produce in the Desert”, and “UAE to Turn Desert into Rich Farmland”, local and international reporting is highlighting the rapid growth that AgTech in the UAE is witnessing. Large indoor oases with lush vegetation are producing vegetables and herbs to feed the local urban population, with a view to export produce down the line – for some at least. These new CEA farms, in many ways similar to Watney’s farm, are often using a hydroponic, aeroponic, or aquaponic[3] system to grow the plants (with or without artificial light) and are offering the option to reduce pressure on imported foods (for example, see figures 4 and 5 below). Focusing mainly on a few select number of crops, such as leafy greens, tomatoes, herbs, and microgreens, such systems claim to reduce water usage by up to 90 per cent while increasing yields and offering pathogen-free produce.

Significant in this new trend is the growing presence of a mixture of incubators, accelerators, and government-backed challenges (such as The CovHack and the Foodtech Challenge, to name a few) to offer a platform to foster AgTech development. Along with financial and technical support in the form of competitions, funds have also been set up, such as a fund of AED 1 billion (around EUR 240 million) from the Abu Dhabi Investment Office, secured by the government, as an incentive for innovation in AgTech (so far, AED 367 million have been invested in 2020 in four AgTech companies). Yet, while some financial support is available, the investors themselves still have to bear the majority of costs. More importantly, projects financially backed by the private sector are developing at a rapid pace.

The farms themselves are often developed by people who could be classified as “white-collar farmers”. With a few notable exceptions, the farm owners, developers, managers, and operators often come from a non-agricultural background. Based on some interviews I conducted in the UAE in 2019, I noted a variety of career paths among the current crop (no pun intended) of AgTech farmers: some worked in the banking and financial sector or occupied managerial positions in large firms; others came from the engineering/technology world. What is common across these firms is the “start-up” character of these companies’ development. These farms – whether developed in the UAE or developed abroad and later implemented in the UAE – tend to follow a similar path: developing an idea and promoting it to attract initial funding, creating a successful trial farm, following up with a second round of seed funding, and finally planning for the growth of the company or for an exit strategy. These new “farms” seem to behave more like some small and nimble tech firm pushing the latest app than like your typical potato plantation.

A central actor driving this new AgTech turn in the UAE is the strategic vision of the government to achieve food security[4]. For the past decade, food security has occupied an important position in the UAE’s governmental strategy. Indeed, food security was the guiding theme of the UAE’s pavilion during the Milan Expo in 2015, in which the government showcased “its experience and achievements in sustainable development and food security”, according to Dr. Rashid Ahmed bin Fahad, minister of environment and water at the time (WAM, 2015). Furthermore, the reshuffling of the UAE cabinet saw the establishment of the Ministry of State for Food and Water Security in October 2017 and the publishing of the National Food Security Strategy 2051 (NFSS) in 2018. The focus of the NFSS is increasing local food production, with a strong emphasis on relying on and developing AgTech. On several occasions, the minister of state for food and water security highlighted the importance of adopting advanced agricultural technologies to ensure the UAE’s future food security.

In many ways, the UAE government is adopting a pre-existing global debate on AgTech. Talk from United Nations agencies such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the International Fund for Agricultural Development, and the World Food Programme all underline the needs and advantages of developing new ways of farming, which rely on high-tech tools and innovative approaches. Indeed, since 2005, several UAE ministries have signed cooperation agreements with international universities, research centres, and the FAO, with the aim to advance research in this domain. These are further supported by a wide range of intermediaries, from research institutions to technology providers, that are at the heart of the AgTech transition. Universities (both local and international); research centres, such as the International Center for Biosaline Agriculture; innovation parks, such as the Sharjah Research, Technology, and Innovation Park; as well as strategic partnership with embassies such as the Agrifood Team for the Gulf Region of the embassy of the Netherlands are all playing different roles in advancing the development of AgTech farms. Numerous conferences and events are organized to connect technology providers, experts, and farm developers.

Post–Covid-19 AgTech Speculation

The discourse on the UAE tends to tell the story of the country through the binary narrative of “plenty” and “scarce”. On the one end of the spectrum, the production and export of natural gas and oil as well as free trade policies present the UAE as a place of financial abundance, which generates enough surpluses and foreign exchange inflows to finance its consumption. On the other end, the environmental context of perceived scarcity and harsh climate conditions, along with a rapidly increasing population, makes the country dependent on food imports, which hover around 90 per cent of the country’s needs. The unfolding of the Covid-19 pandemic represents a considerable threat to the access to food. The Covid-19 pandemic, much like the food crisis in 2007/08, has exposed the vulnerabilities of the global food system. While coverage of supermarket raiding and trade disruptions increased in the early months of 2020, reporting on local food systems’ potential has obtained increased attention. In the UAE, with the exception of a few news items regarding hoarding by supermarkets, it appears that the Covid-19 crisis has had limited impact on access to food. What is more, there are increasing reports on investments in AgTech and on the preparedness of the UAE, whose national food security strategy was proven to work – at least according to the governmental discourse. Time will tell whether the UAE truly is prepared for crises like the one the world is currently experiencing.

The important question that remains for now is can AgTech provide a significant amount of food to limit food import and feed its local population? While the scientific answer to this is yes – arguing that any crop can be grown using CEA, including wheat, rice, and fruit – it does not remain economically feasible at the present time. The challenges of AgTech today are mainly about shifting the focus away from high-end product, encompassing a wide variety of crops while, at the same time, reducing the capital-intensive and operation costs that are so far a limiting factor for such farm development. As far as AgTech is concerned, the UAE is a great big experiment everyone can follow to see if these challenges can be met.

Cynthia Gharios is a PhD candidate in Global Studies at the Graduate School Global and Area Studies.

[1] In an article, Shamsian (2015) points out the limited feasibility and achievability of such a system – due for example to the chemical components on the soil on Mars and the pathogen content of human biowaste (Shamsian, 2015). Moreover, the high amounts of radiation on Mars would render farming impossible (Bennett, 2015).

[2] The UAE ranks 31st in the Global Food Security Index for 2018 (The Global Food Security Index, 2018).

[3] These are three different methods of growing: hydroponic uses mineral nutrient solution in water solvent instead of soil, aquaponic uses aquaculture with hydroponic, and aeroponic uses an air or mist environment.

[4] According to the FAO, “Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food which meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” (FAO, 1996).

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References:

BayWa AG. (2018, September 24). Leuchtturmprojekt in den Emiraten: BayWa und Al Dahra ernten erste Premium-Tomaten in der Wüste | Nachricht | Nachrichten | BayWa Deutschland. BayWay.de. www.baywa.de/news/nachrichten/nachricht/article/leuchtturmprojekt-in-den-emiraten-baywa-und-al-dahra-ernten-erste-premium-tomaten-in-der-wueste/

Bennett, J. (2015, October 6). Rocket Scientists Fact-Check ‘The Martian.’ Outside Online. www.outsideonline.com/2023396/how-accurate-martian

Dennehy, J. (2019, March 27). First farmer of Saadiyat Island tells of miracle crop growth in the Abu Dhabi desert. The National UAE. www.thenationalnews.com/uae/heritage/first-farmer-of-saadiyat-island-tells-of-miracle-crop-growth-in-the-abu-dhabi-desert-1.841900

Fenelon, K. G. (1973). The United Arab Emirates: An economic and social survey. Longman.

Koch, N. (2019). AgTech in Arabia: “spectacular forgetting” and the technopolitics of greening the desert. Journal of Political Ecology, 26(1), 666–686. doi.org/10.2458/v26i1.23507

MacLean, M. (2017). Spatial Transformations and the Emergence of ‘the National’: Infrastructures and the Formation of the United Arab Emirates, 1950-1980 [PhD thesis]. Department of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies New York University.

Shamsian, J. (2015, October 2). Fact-Checking “The Martian”: Can You Really Grow Plants on Mars? Modern Farmer. modernfarmer.com/2015/10/can-you-grow-plants-on-mars/

The Global Food Security Index. (2018). The Global Food Security Index. foodsecurityindex.eiu.com

UAE Minister talks plans to build a “Silicon Valley” of food technology. (2018, September 21). Inspire Middle East - Euronews. www.euronews.com/2018/09/21/uae-minister-talks-plans-to-build-a-silicon-valley-of-food-technology

WAM. (2015, June 6). Milan Expo 2015 an opportunity to showcase UAE’s experience, achievements in sustainable development, food security. Wam. www.wam.ae/en/details/1395281524776